Building a World Model of Consequence

This is a working note on how I think about world models: what they are, how to train them, and how they sit alongside agents. It’s written for a technical audience, and many of the ideas borrow from human learning.

Humans carry an internal sense of how the world responds to actions. We use it when we enter a new environment, make a decision, or look back on what happened. We form a map and make simple predictions like, “in this state, if I do X, Y tends to happen.”

This sits at the core of human learning. We act in stateful environments (metacognition), get feedback (process feedback), and update an internal world model of consequences. It is a map of “if I intervene here, this is what changes.” This is the same basic pattern as CausalARC: reasoning tasks are sampled from a causal model, and the learner uses observations, interventions, and counterfactuals to solve them.

I’ve spent the last year building these primitives into software. My work on Atlas focuses on continual learning for AI systems. The goal is to enable LLMs to learn from their own actions in real time and update their behavior.

This research pushed me toward two conclusions:

- Learning from trajectories compounds. You learn from actions and outcomes, then apply that across similar situations.

- A lot of the value comes from how you assess learning and structure experience.

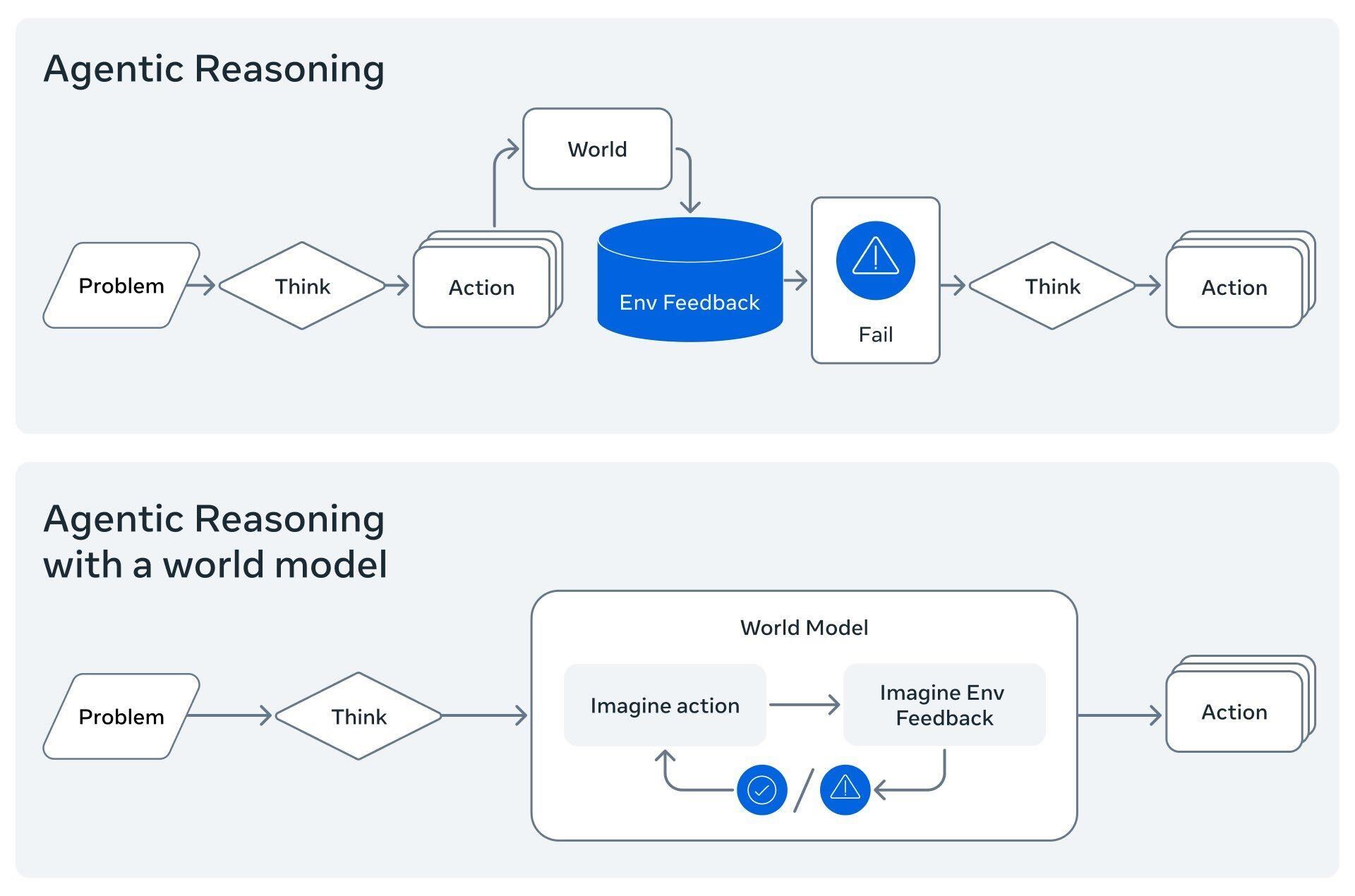

Most agentic systems today (Atlas included) are policy learners. They react to feedback and adjust what to do next time.

Humans also plan. We think ahead. We ask what happens if we take an action. For an AI system to do that, it needs a reusable, explicit understanding of how the environment behaves. It needs to know, in a structured way, that “if I click this button in this admin console while logged in as finance, a wire will be sent.”

This is the role of a world model of consequence. Below I define what I mean by a world model, then describe a training pipeline using AI browsers as a proxy environment.

What I Mean by a “World Model”

From a technical perspective, a world model is a learned model of how an environment responds to actions:

Given a state

sand a candidate actiona, predict what happens next and why.

Formally you can think of it as approximating something like P(next_state, consequences | state, action), with a bit more structure on the outputs. In the language of causal modeling, it approximates the environment’s transition dynamics: “if I intervene with action a in state s, here is the distribution over downstream states and outcomes.” For AI browsers and other tool-using agents, I focus on consequences:

- What state transitions will this action trigger?

- What sensitive data or capabilities are touched?

- Does this look like a prompt injection or memory-poisoning pattern?

- Are there safer alternatives that would still achieve the user’s goal?

If you’ve read Meta’s Code World Model work, this is the same pattern: train a model on execution traces so it learns what code does at runtime.

The browser is just another environment:

- State: URL, Document Object Model (DOM) snapshot, auth context, network events, local storage, prior steps.

- Action: click, type, navigate, submit a form, run script, call a tool.

- Next state: a new page, different auth state, changed database rows, network calls, etc.

Most current agents treat that entire transition structure as a black box. They call tools, observe text, and maybe maintain some scratchpad memory, but they don’t maintain a reusable model of how the environment works.

That leads to three failure modes I’ve observed in production:

- Re-discovering the same environment over and over. Every new session becomes a fresh trial-and-error loop, even in the same admin console or internal SaaS. This happens even with the same tools and persistent memory.

- Weak credit assignment. Systems record success/failure at the end of workflows, but not which specific

(state, action)caused what downstream effect. - No reusable notion of consequence. Guardrails are usually text classifiers over prompts, not learned mappings from

state, action → consequence.

A world model tackles this directly. It enables an AI system to simulate the outcome of actions before ever committing to it in the real environment.

Image Credit: Adapted from Meta’s Code World Model.

Image Credit: Adapted from Meta’s Code World Model.

World models have their roots in robotics and physical AI. In self-driving, we build “digital twins,” simulations where an agent can crash a thousand cars to learn how to drive one safely. Work like NVIDIA’s Cosmos formalizes this: train a foundation model of physics so an agent can plan in a learned reality before touching the real world.

I use the browser as a proxy environment for consequence modeling. It sits at an intersection of:

- Untrusted Content: The open web (news, social, malicious sites).

- Powerful Tools: The ability to execute code, transfer money, and modify infrastructure.

- Elevated Credentials: The identity of the user (auth tokens, cookies, sessions).

Prompt-injection and related AI security issues show up again and again:

- Hidden DOM text telling the agent to exfiltrate data.

- Cross-origin forms abusing the agent’s authenticated session (agent-mediated CSRF).

- Local storage and service workers quietly poisoning future sessions.

- Crafted URLs and omnibox entries that smuggle instructions into “normal” navigation.

In this domain the core world-model question is literal:

“If I click this, what will happen?

If I navigate here, what will that unlock?

If I submit this form, who gets the data?”

That’s exactly the question we want agents to be able to ask and answer before acting.

A World-Model Interface for Agents

An agent-first world-model interface for this domain looks like:

predict_outcome(state, action) -> {

risk_label, // "safe" | "unsafe" | "uncertain"

risk_score, // float in [0, 1]

rationale, // step-wise reasoning and explanation

counterfactual_action,

predicted_consequence,

state_delta

}

risk_label/risk_score- is this action safe, unsafe, or uncertain?rationale- a step-wise explanation grounded in the current state.counterfactual_action- a safer alternative (including no-op) the agent could take instead.predicted_consequence: a narrative plus tags describing what the model thinks will happen (e.g., “data_exfiltration → payroll_data → external_host”).state_delta: what the model expects to change in auth context, network events, storage, etc.

The runtime loop looks like:

- Policy agent proposes an action in the current browser state.

- Agent calls

predict_outcome(state, action)on our world model. - World model returns risk, a short consequence description, and (optionally) a counterfactual.

- Agent either:

- Executes the original action, or

- Switches to the counterfactual, or

- Escalates to a human, depending on risk and configuration.

How to train a browser world model

The training pipeline is evolving as the research landscape shifts. The pattern I keep coming back to has four stages: early experience, Socratic supervision, mid-training, then multi-task Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT).

1. Early Experience: Coverage & Dynamics

The first goal is simply to understand the environment’s physics. We need coverage, broad exposure to states and transitions, without the bottleneck of human labeling.

I roll out a baseline browser agent (backed by a strong base model) in browser environments and record:

- The state summary before each action.

- The action dict.

- The transition summary and next state.

This is what the Early Experience paper calls reward-free interaction data: trajectories generated by the agent itself, without requiring a scalar reward.

In practice, this gives us thousands of episodes per site, mixing benign workflows and accidental edge cases. In this phase, I do not ask the model to judge risk. I want it to model the dynamics:

“Given I am on this page… and I click this target, what state am I likely to see next?”

This generates a massive dataset of raw transitions that grounds the model in how the browser actually behaves.

2. Socratic Attacks: Causality & Supervision

We still need causal judgment about whether an action was dangerous or optimal.

For that, we add a Socratic supervision layer, inspired by Socratic-Zero. We take the raw traces from our coverage runs (or generate new attack-specific ones) and have a stronger “Teacher” model annotate them with rich causal reasoning:

- Risk: Is this action safe/unsafe/uncertain?

- Consequence: What are the likely downstream effects?

- Counterfactual: What would a safer alternative look like?

- Rationale: Why is this the case?

This transforms a raw (state, action, next_state) tuple into a supervised lesson. The teacher explains the causal structure of the risk. These traces give us the targets we need to train the world model interface defined above: risk scores, rationales, counterfactuals, and consequence labels.

3. Mid-Train + Multi-Task SFT

Now we get to training. From a dataset perspective, we merge early-experience episodes and Socratic traces into two datasets:

- A mid-train dataset of transition-focused examples:

state_summary,action_repr,next_state_summary, optional teacher rationale, and a weight from the Socratic curriculum.

- An SFT dataset of decision-focused examples:

state_summary,action_repr, and labels for:risk_label,risk_scorerationalepredicted_consequencecounterfactual_actionstate_delta

We use the Early Experience data for a mid-training stage that moves the base model toward the browser transition distribution. Then, we use the Socratic traces for multi-task SFT, treating the world model as a multi-head predictor:

- One head classifies risk.

- One generates rationales.

- One predicts structured consequences.

- One proposes counterfactual actions.

- Optionally, one predicts structured state deltas.

This is where the model learns whether an action is dangerous, what the downstream effects look like, and what to do instead.

4. On-Policy Distillation

Multi-task SFT gives you a solid supervised world model. The natural next layer is to let the model keep improving on the states it visits when coupled to a policy.

Conceptually, an on-policy distillation stage for a browser world model looks like:

- Treat the current world model (or a separate student) as the student.

- Let the Socratic Teacher (or a stronger ensemble) score and comment on the student’s predictions on real rollouts.

- Optimize the student to match the teacher’s distributions and rationales on those student-visited states.

Done carefully, this bridges the gap between pure supervised world modeling and full RL. You get experience-driven improvement with a stable, sample-efficient optimization loop. RL can still sit on top for reward-rich slices. On-policy distillation will likely do most of the work.

What “Good” Looks Like in a World Model

It’s tempting to define “good” world models in terms of task metrics: success on a fixed benchmark, goal completion on a known distribution. Most existing evaluations do this.

The biggest learning I’ve had so far is that this misses what makes world models interesting.

Empirically, world models seem to benefit more from high-volume, slightly messy exploration data than tiny, pristine, task-specific datasets. The model learns the environment’s dynamics from broad exploration, then transfers that understanding to whatever tasks you care about.

Under that view, “good” comes down to a few questions:

- Has the model actually internalized the short- and long-term implications of actions in this environment?

- Can it reuse that environmental understanding to solve novel tasks it wasn’t explicitly trained on?

- Does its notion of consequence transfer when you change goals, agents, or surface tasks, as long as the underlying environment is the same?

That’s a different evaluation mindset. You start asking “how well does the world model’s knowledge of this environment generalize to new goals and perturbations?”

This is exactly the kind of question NVIDIA’s Cosmos evaluates physical world models on 3D consistency and object kinematics, ensuring the model respects the laws of physics rather than just generating plausible pixels.

For browser agents (and other real systems), we need analogous dynamic, fluid benchmarks that can:

- Generate new tasks and attack patterns from a shared environment schema.

- Vary goals and constraints while keeping the underlying dynamics fixed.

- Measure end-task success and how effectively the world model’s learned environment knowledge applies off-distribution.

What I’ve shared so far is one concrete attempt to line up training and evaluation with that philosophy. You design a learning environment, give the model time to explore and see consequences, and test whether the model generalizes its knowledge of the environment to new goals and perturbations.

Browsers as a Proxy for where we’re heading

If you view browsers as a proxy for agentic environments, a few assumptions about the future are:

- Agents will learn from their own trajectories. We already see early evidence of this.

- World models turn experience into reusable structure. Agents build a persistent model of how an environment behaves under actions.

- Planning-capable agents will internalize these world models. Agents embed these capabilities internally for planning and decision-making, similar to autonomous systems in continuous control.

Browsers are just one of the early surfaces where this is both urgent and measurable.

Open Questions

World models are not a cure-all. They do change how we engineer agentic systems. As we solve the technical hurdles, the questions shift from implementation details to what we do with the capability:

-

What are the implications of generalized world modeling? Today we build specific models for specific risks (security, fraud). A robust world model could act like a common sense layer for digital environments. Once an agent understands consequences across many environments, does it pick up broader reasoning skills? How does that change how we build and apply AI systems?

-

How does this change Human-Computer Interaction? If an agent can simulate consequences, the nature of delegation changes. We move from “human-in-the-loop” (checking every step) to “human-on-the-loop” (reviewing predicted consequences before approving a plan). Trust shifts toward the model’s understanding of risk, similar to how engineers interact with coding agents today.

-

How do we evaluate causal understanding? This is the hardest unsolved problem. Standard metrics measure outcomes. We need benchmarks that test whether an agent understands why it succeeded, or whether it memorized a winning path. Games and open-ended digital environments are a natural place to revisit, and this will take time.